Dad

Just after Thanksgiving, my dad, William Edward “Buster” Klinkenberg, passed away at the age of 87. Dad had been remarkably healthy and active for his whole life, but started suffering from ALS early in 2022, and succumbed to a rapid decline the last few months.

Obviously, you can’t reduce a person’s whole life to a short column. But, I wanted to take a little time to write about him, about our relationship, and what this all means for me. I know this doesn’t cover the usual ground for my site. But there are aspects to get into that do, I think, offer some lessons for people trying to improve our communities and our world. Also, it’s helpful for me to just write some of this out – call it a bit of therapy if you wish.

At some point, we all lose our parents. If we’re lucky, like my family has been, we get to live a lot of really good years together. Some people never even really get to know their parents. Some people lose them at a very young age, or even in their formative years. I’ve had friends that fit all those descriptions. So, I’m keenly aware of how fortunate I’ve been, and our family has been. Still, at the end, you can’t help but feel a tremendous sense of loss. Even when the outcome is obvious, it’s still very difficult.

Dad had a big personality. He had a remarkable ability to chat up just about anyone in any circumstance, and even have difficult conversations with people. Often, he would force those conversations to happen – even the “third rail” topics of politics and religion. He really enjoyed learning how other people think and see the world. And, he also really enjoyed just debating and poking holes in an argument. Many times, when we were younger, I wasn’t actually sure how Dad felt about something we were discussing or debating. He was very good at playing Devil’s advocate. And he had a unique ability to take something complex, make a simple argument, and really make you feel like you had no idea what you were talking about. He could devastate those of us, like me, who sometimes make everything overly complicated.

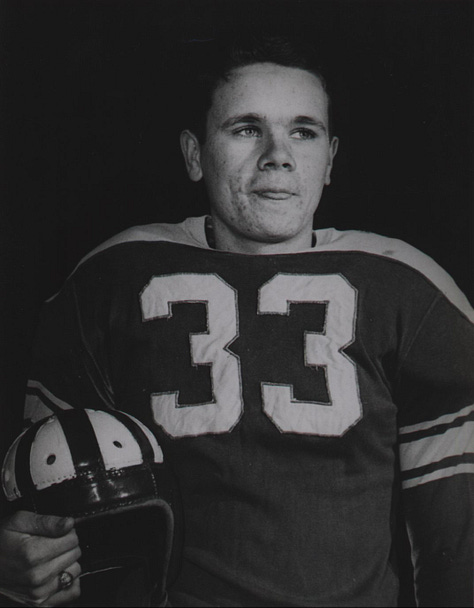

Dad never went to college. He was a star athlete in a tiny town in rural Kansas. Or at least, what used to be rural Kansas, and now is an exurb of Kansas City. He played all the major sports as a kid, but was especially good at baseball and football. In Basehor, his hometown, in the 1950s, football was a very different game than today. He played 6-man football, which is something that disappeared with school consolidation in the 20th century. He ostensibly had some kind of record for touchdowns scored in 6-man football, though none of us have actually been able to verify this. Sports records in small town America weren’t as thorough in the 1950’s as they are today. Interestingly, 6-man football has reappeared in Kansas in the last few years as more of the state has faced population decline. Check it out - it’s a pretty wild version of the sport.

Basehor was nothing more than a dusty little agricultural town, like so many towns all over America. It had a few hundred people living there in his youth. His Dad ran a service station and drove a school bus. The town had a handful of little stores on its Main Street, and not much else. Dad’s brother George would later say, “we grew up poor but didn’t know it.” George was one of four siblings my Dad had, two of which still survive. Dad always had a fondness for where he grew up, even long after he left home. In fact, one of his passing wishes was to set up a scholarship fund at Basehor-Linwood High School, in honor of his parents.

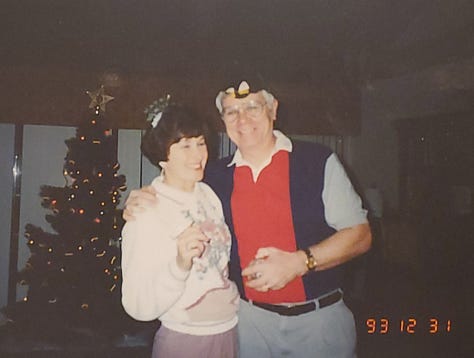

Like so many in his generation, he joined the military not long after high school. In those in-between years, he met my Mom (an incredibly star-crossed love story, which perhaps I’ll tell another time), and they were married on Christmas Eve, 1957. Soon after, they were off to Germany for a two-year tour in the Army.

He had the good fortune to be in the Army in between our various foreign wars, so his time was filled with adventure and friends. My Mom and he have often referred to their time in the Army as their “two yearlong honeymoon.” They traveled all over Europe in the years it was still rebuilding from the devastation of WWII. That experience planted a seed that lasted a lifetime for them (and for us kids), of wanting to travel and see as much of the world as possible.

In Germany, the first of four kids were born. My sister Cindy was born on the base in 1958. Later came Theresa, then Dean, and finally I arrived in 1969. We like to say, I was the happy accident. Or maybe, I like to say that.

When they came home from Germany, Dad went to work for Wilson Foods (a meat-packing company) as a clerk in Kansas City, Kansas. I’ve had so many conversations with friends and acquaintances over the years who assumed we were a military family. It’s a logical assumption to make, because we moved constantly. People didn’t get my joke, “No, we’re not military – we’re meat packing.”

We moved so much because that’s how Dad was able to get promotions and move up in the company. Mom and Dad sacrificed a lot for all of us – the stability we might’ve had with a more “regular” job; their own happiness in one city or another. But they did it so we could all have a better life. And we did. We lived in Kansas, Omaha (where I was born), Oklahoma, Kansas again, Minnesota, and finally in Missouri. Marshall, Missouri was Dad’s last stop with Wilson Foods, where he had worked up to be Plant Manager.

Wilson Foods was ultimately bought as part of one of the very common leveraged buyouts in the 80s and early 90s, and broken up into pieces. The purchaser, Doskocil Foods, kicked Dad to the curb after 35 years with Wilson’s, and brought in their own management team. I’ll never forget the local newspaper had a front page headline, “Klinkenberg Fired.” Mom was furious at the paper for doing it in that manner. It seemed unnecessary, but then, it was big news in a small town.

Dad was never one to sulk, or to sit around. He pretty quickly reinvented himself, and became an entrepreneur. In fact, he’d always had a long desire to be his own boss. With money they’d saved, he purchased a gas station (following in his Dad’s footsteps) in Independence, Missouri, and later a second. He ran both stations right up until he decided he’d had enough of dealing with Amoco, and ultimately retired.

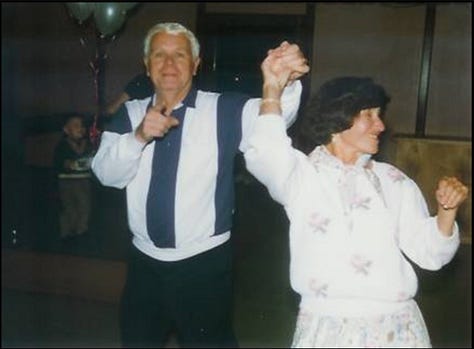

Given how active he always was, none of us had any idea what retirement would look like. He was not a person to just sit still and do nothing. And of course, he didn’t. Sure, they traveled, and sure, he played golf and played a lot of cards. He always had a very strong competitive spirit, and that was more often than not rewarded with victories. But he also rediscovered his old passion of playing ball; not football – softball. Dad was extremely active in Senior Softball leagues, right up until his passing. He played with the KC Antiques, often three times a week. Naturally, he also had to get involved in the administration of the organization – that’s just how he was. Some of you that know me personally might say – “gee, that sounds familiar, Kevin.” It’s true, the apple doesn’t fall far from the tree.

During all these times, and especially during retirement, my parents have been a rock in our lives. They help us when we need it, they support us, but also question and push us. They’ve never been afraid of challenging conversations. I can’t express how lucky I am to have had such wonderful parents. They’ve shaped almost everything of who I am, what I value, and how I’d like to be better.

Since his passing, I find myself doing the kinds of things that others probably do after a loss. For example, Dad liked country music. I’ve never really much liked country music. OK, truth is, I’ve hated it for most of my life. We all used to make fun of him for it, or groan out loud when he put it on the car radio. But now I find myself listening more and more. Funny how that happens.

Often, something comes up that immediately makes me think of a conversation we had, or one I’d like to have. Perhaps it was a debate that was unresolved, or a fun, shared event. I think, “dammit, this is the point we really need to hash out!” I’d like to talk with him about it, but then realize I cannot. So it goes.

Reconciling Differenes

Of course, like any parent-child relationship, there were some important ways in which we were different, too. We share a lot of personality traits, but not all of them. He loved his newer houses in the suburbs – I like my old houses in the city. He liked ice cream with nuts. I think ice cream should be topping and nut-free. He and Mom had pretty typical husband/wife roles for their era. I’m more in line with how things are today. I don’t judge whether one era is right or wrong. We could all stand a little more humility about our own time and place. But how we navigated our relationships is definitely different.

Dad grew up in a time when so much of America and our society just worked well. Our country was ascendant, and rife with confidence after winning WWII. While his political views shifted over the years, he pretty much always had faith in the big, centralized forces that defined America for most of the 20th century. He watched the evening news, read the local paper, believed in America’s ability to do big things (and do them well), and trusted our democratic institutions. Even if he disagreed with them, which he frequently did, he had trust in our country being able to solve problems and work out differences.

I don’t share all those views, and we frequently differed about possible solutions or ways forward. I was born into an era when those institutions, and the idea of a certain kind of America, was starting to fail. It was obvious to me there was a gulf between the promise and what I saw in reality. The cynicism of Generation X was largely shaped by those of us who noticed all this. I did, in fact, have to remind Dad in his later years, that he used to tell us, “Don't believe anything you hear and only half of what you see.” Yes, that has stuck with me all these years, and I think it’s wise advice.

I’ve written about this more, here, and why it’s dangerous to romanticize the 1950s and 60s. I think Dad thought this type of thinking was too fatalist. I view it more as facing reality. I don’t begrudge him or anyone of his generation having their views. It makes complete sense, growing up in the world they did, to have a deep faith in America’s ability to do big things, and do them well. We absolutely need that viewpoint! I simply think, times change, and we left that world a long time ago.

That’s not all to say I think everything is hopeless. To the contrary, I am and have always been an optimist. I have a strong belief that truly free societies eventually correct and figure things out. But, my perspective is more that we’re in a “Fourth Turning” time period now, and there’s no fixing our current big dilemmas. They will resolve themselves one way or another, and society will pick itself up and create something new. That’s part of the essence of my “America 6.0” presentation. Dad, on the other hand, felt most of our big issues could be fixed, and pretty simply. And he would often make a very compelling argument in his favor.

His perspective is actually one I’d prefer to have. I want to have trust in leaders, in institutions, in news media. But, it’s been obvious to me for quite some time that the logical position today is to be highly skeptical of most everything coming out of our big systems, and especially large media corporations. If you believe the polling, the vast majority of people agree with me. Events in recent years have only exposed this to more and more people, and deepened our societal angst. My Dad’s viewpoint is literally dying off, which is sad and a challenge for us all.

Again, I don’t mean to be doom and gloom. That’s not who I am. I’ll have much more to say about all this over time, and what it means for our communities. But in short, any of our democratic institutions that get more heterodox, that avoid groupthink, that get leaner and closer to the people they are meant to serve - I think those will thrive. Those that don’t, are in for a very difficult time period. Our institutions (and large corporations) have become far too focused on serving their own staff, and thus have become less capable of solving real problems for real people. In fact, our institutions (and this includes the news media), frequently don’t even want to see or acknowledge the real problems that exist, as it might challenge their worldview.

I’ve written elsewhere that I think American society is broadly experiencing what a wealthy family goes through. The first generation makes it, the second generation spends it, and the third generation blows it. Then, people pick up the pieces and rebuild. That’s the essence of the “fourth turning” theory.

That may not seem like a good thing to many of you reading this. Maybe it’s not. But reality often doesn’t care about what we wish to be true. Part of the human condition is the cycle of birth, life and death, and then birth again. We do this as people, as communities, and as human societies. Even a cursory reading of human history reveals this. So it goes.

The broader point, though, is that my Dad and I could have these kinds of conversations. We could disagree about all this, sometimes strongly, and still love and respect each other very much when it was all done. Wouldn’t it be nice if this was more common? Can we do this with people who aren’t family?

Acknowledging Wisdom

There’s an arc to our family storyline that is actually just very typical for a lot of European immigrants to the US. We escaped a situation that my ancestors wanted to avoid – all the endless European wars of the 19th century. The Klinkenbergs found land for themselves in the middle of the country, casting off their old lives and building new ones. Through very hard work, lots of kids and probably some luck, they gradually made their way into the American middle class. My parents and their siblings nearly all moved on from the dusty, small town life to become part of the great postwar American boom. They enjoyed new houses, new cars, and lives filled with travel that their parents could hardly imagine. My generation is no doubt a little softer and has higher lifestyle expectations. Our kids? Likely even another step softer with even loftier lifestyle expectations.

It's impossible to go through the experience of losing a parent and not consider your own mortality. What kind of a person am I? What kind of father? How many good years might I have left, and what do I want to do with them? What kind of life do I want to lead? These are all questions that’ve been rolling around in my head lately. I feel a phase turning is coming – in life, in society, and perhaps in me, too.

There are ways in which I want to be more like my Dad, and I hope to do so. I want to have more open-minded conversations with people. I want to be a better leader, which he was. I want to focus more on family and friendships, which is frankly so much more important than anything else in life. I enjoy challenging people, but need to learn to do so more in the manner he did. Dad always had a smile or a laugh ready to go, and a great way of lightening up a situation. Even toward the end, when he had no quality of life at all, he found time occasionally to smile and laugh.

Dad was a serious guy, but also really knew how to have a good time. He created a fun bet years ago amongst those of us in the family. When we would argue about what might happen with sports, or current events, or politics, we would bet on it. The loser of the bet would have to acknowledge the Superior Wisdom of the winner, in front of the family. I lost my fair share of those, and won some, too. I’m happy to say I won the last one, and made him smile a bit when he had to acknowledge my superior wisdom in his last days. He did it begrudgingly, and even made a joke about it.

Dad was a big personality in the lives of most everyone he interacted with. We’ll all miss him greatly, and know that our lives will never be the same.

Whatever happens in your world, thanks for taking the time to read this and other posts I’ve produced over the years. It’s been my pleasure to share my thoughts in this space, to have people read and share them, and to open a few minds in the process. I look forward to much more, along with reasonable (even passionate) disagreement as we all try to make our communities better places to live. Here’s to you, Dad. I miss you, but carry you with me forever.

Sorry for the passing of your Father. Great testament and hope you are doing well.

Jeff Haney

I am so sorry for your loss. I too lost my father in 2022 and have been processing my grief, loss, and next steps. As someone who worked with and for you all those years ago, I congratulate you on your professional and personal journey. I find myself mulling over the same thoughts you share about your legacy, impact, and place. As an optimistic realist, I have scaled down some early delusions of grandeur and focus on the beauty of moments, slivers of opportunity, and most of it has been due to the birth of my almost six-year-old son. Prior to Hayden I was a stepdad, and those rules of engagement and relationships are different. Not bad or worse, just different.

Anyway, I really glad I stumbled onto this story. My relationship with my father was sadly not as open as yours was and I'm having a hard time processing how I feel. For years I tried to get to know him but he was reluctant to talking on the phone (we lived 1100 apart), emailing, or texting. Those rare times I was able to get back to Kansas City he would often be sleeping towards the end which only scared and frustrated me more.

For others who may read your article and read this, I am finding two things helping me through this: first, at the recommendation of a dear friend who lost her husband also last year, I listened to Anderson Cooper's podcast on grief. I believe it's called, "All there is"; and two, in the final episode of that podcast I learned from one of his listeners to write a letter to myself as if my father wrote it. I haven't started yet, but I'm beginning to like the idea of putting all those unanswered questions to rest. Maybe then I too can let him rest and allow me to learn more from him as I tell my young son stories of my father, and the impact he had on me.

Thanks again and all the best to you and your family. Again, my sincerest condolences.